Energy Audits for Council & Government buildings. What Is Different

Government and council buildings operate under different pressures than private commercial assets.

Budgets are publicly scrutinised.

Procurement is structured.

Capital works are planned years in advance.

Energy performance is increasingly visible through NABERS and public reporting.

An energy audit in this environment must do more than identify savings. It must support governance, compliance, and defensible decision-making.

This article explains the differences between energy audits for government and council buildings in Australia and how to structure them properly.

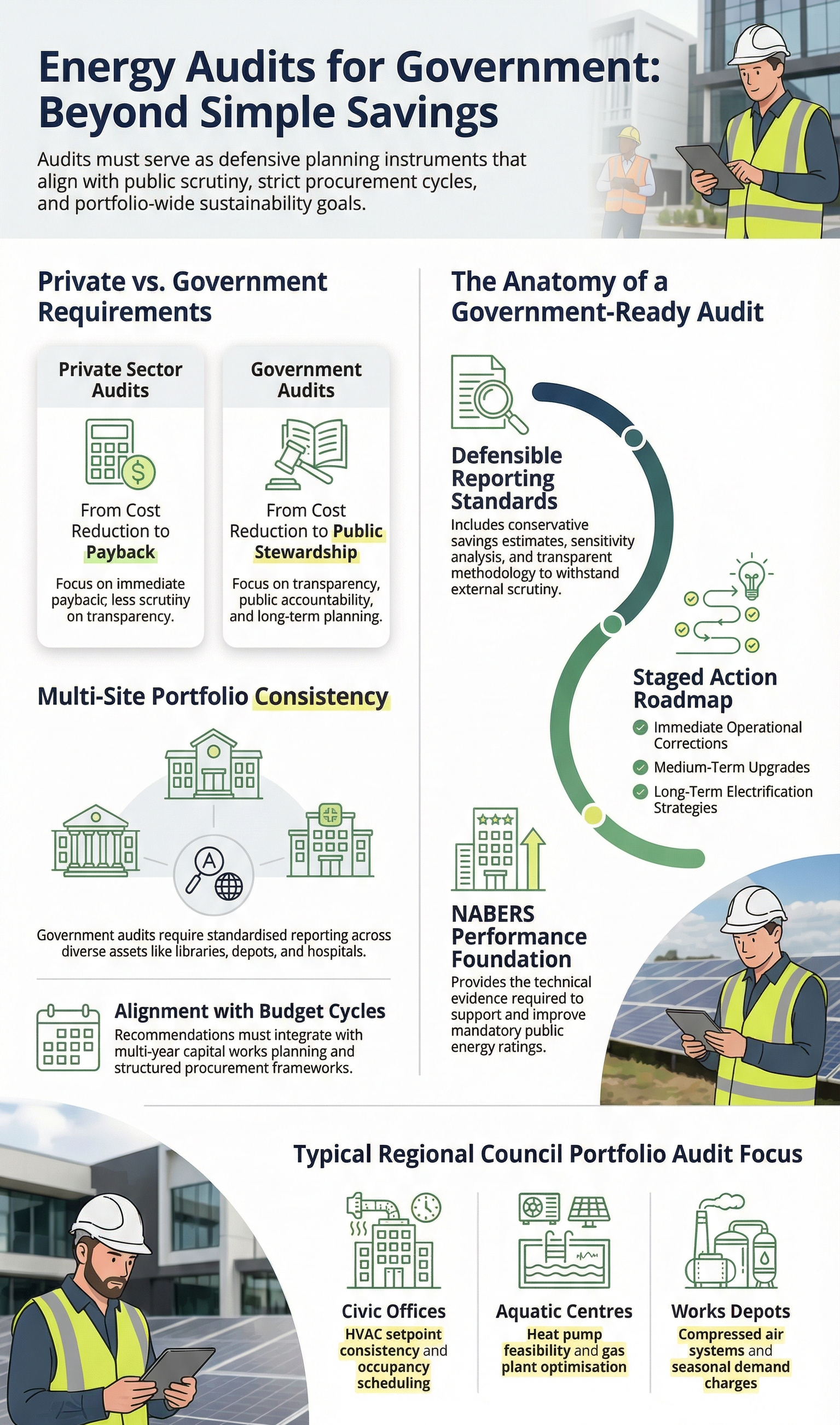

How government & council buildings differ from private commercial sites

Most private sector audits focus on cost reduction and payback.

Government audits must also address:

Transparency and public accountability

Alignment with long-term asset management plans

Multi-site portfolio consistency

Procurement and funding cycles

Grant eligibility and co-contribution requirements

The technical systems may look similar. Offices still have HVAC, lighting, pumps, hot water, and controls.

What changes is the decision environment.

If you are managing a council or state portfolio, you are not just reducing energy. You are managing risk and demonstrating responsible stewardship of public assets.

Single-site versus portfolio-wide audits

Government asset owners rarely manage one building.

Typical portfolios include:

Civic administration buildings

Aquatic centres and leisure facilities

Works depots and workshops

Cultural facilities

An isolated audit on one site may deliver savings, but it does not provide portfolio insight.

In most government environments, the stronger approach is staged, portfolio-aligned auditing.

This includes:

Consistent methodology across sites

Standardised reporting formats

Comparable financial metrics

Clear ranking of opportunities by risk and return

Alignment to capital planning cycles

For more on the broader audit framework, see Commercial and Industrial Energy Audits Australia.

What an energy audit must deliver in a government context

In government, the report must stand up to scrutiny.

That means:

Clear assumptions

Conservative savings estimates

Transparent methodology

Defined implementation risks

Sensitivity analysis where required

Decision makers may include:

Asset Managers

Councillors or Board members

Procurement committees

External auditors

The audit needs to translate engineering findings into commercial and governance language.

Light technical detail is important. Decision clarity is more important.

How audits support NABERS improvement plans

Many government offices and council buildings are rated or required to be rated under NABERS.

An energy audit plays a practical role in improving performance.

It helps:

Identify base load issues

Diagnose HVAC inefficiencies

Review after-hours energy drift

Validate control strategies

Prioritise staged upgrades

An audit provides the technical evidence required to support a credible NABERS improvement plan.

If you want to understand that connection in detail, see How Energy Audits Support NABERS Improvement Plans.

Importantly, the audit is not the rating. It is the technical foundation that allows you to improve the rating with confidence.

Operational constraints in government facilities

Government and council buildings present unique operational challenges that affect how audits are conducted and how recommendations are implemented.

Access and scheduling constraints are often more restrictive than in private buildings. Libraries operate during public hours. Council chambers host evening meetings. Aquatic centres have limited shutdown windows. Works depots run continuous operations.

This affects audit timing and the depth of investigation possible during site visits.

Contractor coordination must align with procurement frameworks. You cannot simply call a preferred supplier. Quotes must be comparable, documented, and defensible.

Shutdown planning for major upgrades requires months of advance notice, coordination with community services, and, often, the temporary relocation of operations.

The audit must acknowledge these constraints and structure recommendations around them, not ignore them.

Indicative example. Council office and library portfolio

A regional council manages:

1 civic office

3 libraries

1 aquatic centre

2 depots

Total annual electricity and gas spend exceeds $1.2 million.

Interval data shows:

Elevated base load across all sites

HVAC running outside occupancy hours

Poor setpoint consistency

High gas consumption in the aquatic centre plant

A structured audit program identifies:

Low-cost scheduling corrections

Control strategy optimisation

Heat pump feasibility for pool heating

Lighting upgrades in high-hour spaces

Demand charge exposure during seasonal peaks

The audit does not recommend replacing all plant immediately.

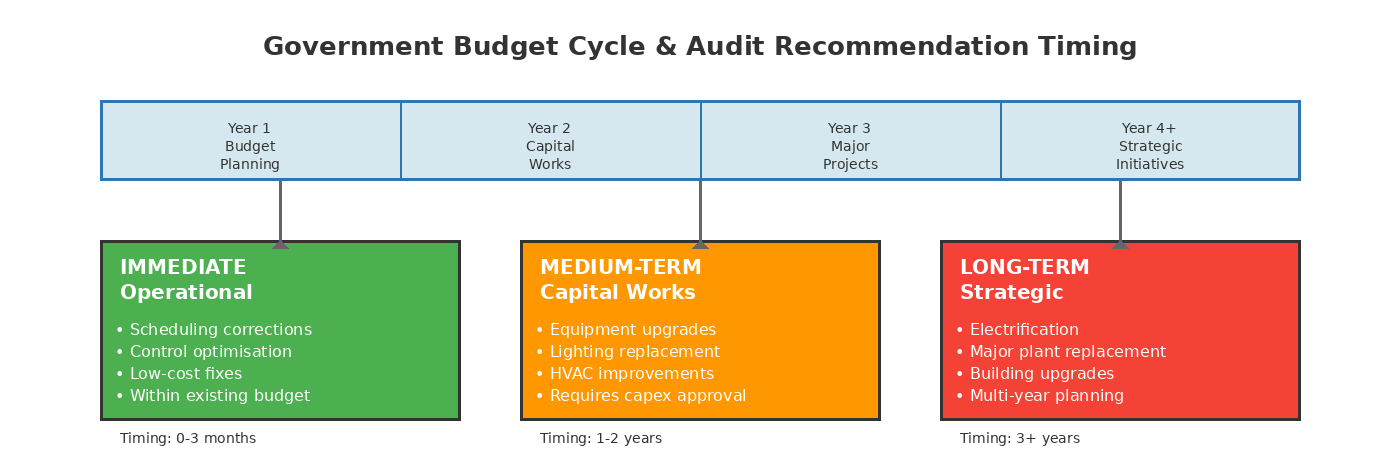

It stages actions into:

Immediate operational corrections

Medium-term capital upgrades

Longer-term electrification strategy

This structure aligns with budget cycles and capital works planning.

That is the difference. The audit becomes a planning instrument, not just a savings report.

Energy audits in asset due diligence

Government assets are often acquired, divested, or upgraded through structured processes.

In these cases, energy audits support:

Pre-acquisition risk assessment

Infrastructure condition review

Capital liability forecasting

Decarbonisation pathway modelling

The same audit methodology can support operational improvement and long-term asset governance.

Budget cycles and procurement reality

Government budget cycles can delay implementation.

An audit must therefore:

Separate operational savings from capital works

Provide defensible cost estimates

Identify quick wins within existing maintenance budgets

Clarify which measures require procurement approval

Overpromising savings in this environment creates reputational risk.

Conservative, evidence-based recommendations build trust.

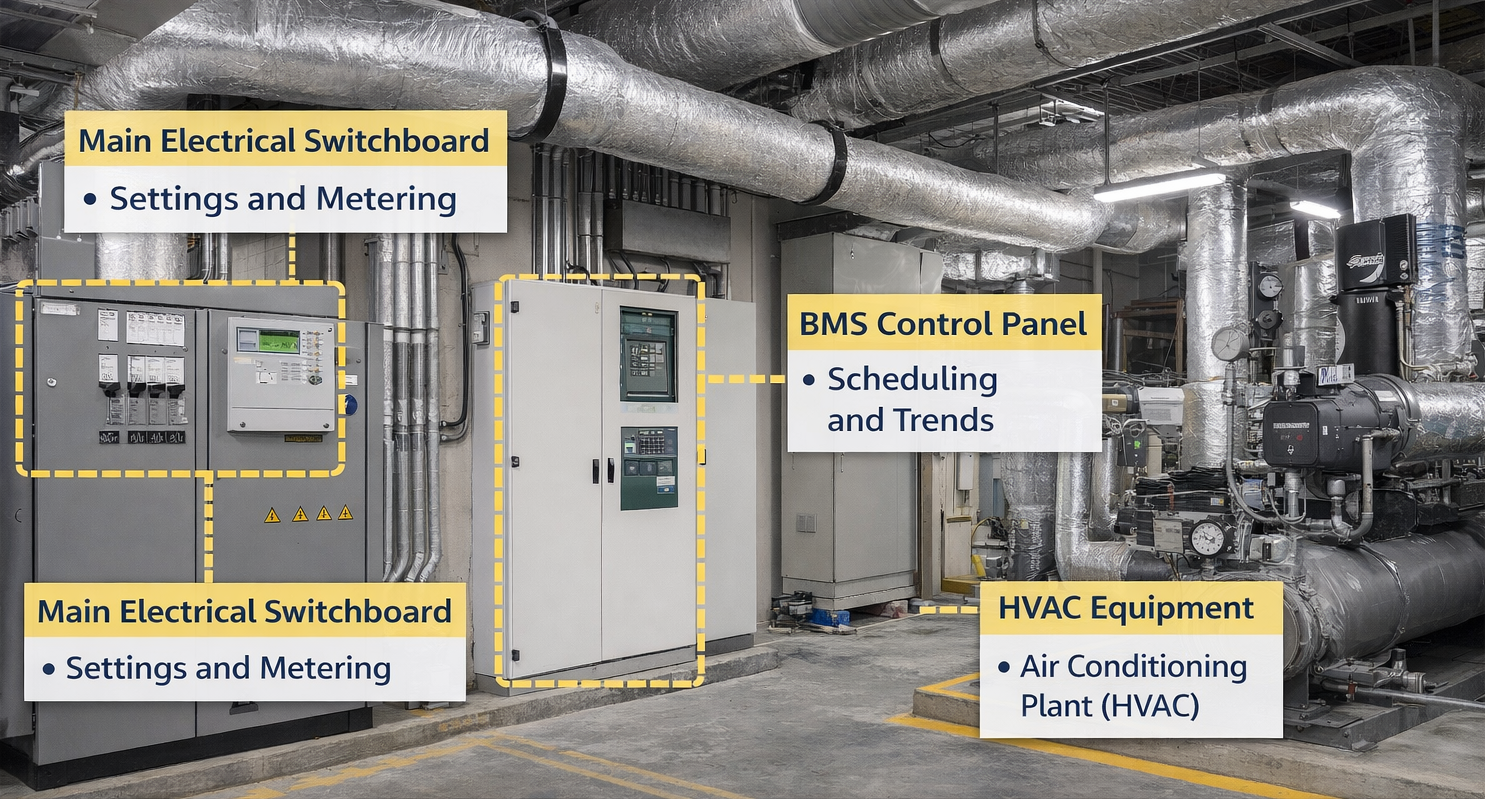

What is not different

Despite the complexity of governance, the fundamentals remain the same.

We still examine:

Switchboards and load profiles

HVAC plant rooms

BMS trends

Compressed air systems in depots

Boiler and hot water systems

Lighting controls

The difference lies in how findings are structured, prioritised, and defended.

Energy audits for government buildings must be technically sound, commercially realistic, and governance-ready.

If you manage government or council assets and want to understand whether a structured audit program is suitable for your portfolio, request a commercial energy audit and discuss your site and planning constraints with us.

Find out about available energy saving grants and subsidies for your organisation on our Grants page.